Chronic low back pain: exercise, walking, or both?

The management of chronic low back pain has always been a popular issue. This article looks at a study comparing different forms of exercise and its impact on low back pain.

The great dread that is low back pain (LBP) will affect 80% of Americans at some point in their life. Especially since the coronavirus lockdown, The LAB has seen a sharp rise in LBP cases due to more people working on their laptops from home.

The study:

A randomized controlled trial by Suh et al looks at the impact of different exercise protocols on individuals with chronic low back pain (>3 months).

Group 1: Flexibility exercise (FE)

Group 2: Walking exercise (WE)

Group 3: Lumbar stabilization exercise (SE)**

Group 4: Lumbar stabilization combined with walking exercise (SWE)**

**SE exercises targeted the transverse abdominis, rectus abdominis, erector spinae, multifidus, internal obliques and quadratus lumborum.

All groups underwent their designated exercise program for 30-60 minutes, 5-6 times a week, for a period of 6 weeks. These exercises were performed on their own at home. All participants were also educated on optimal posture and the abdominal bracing method, which was encouraged to be used throughout exercise.

The main outcome measures were subjective pain (VAS) during rest and physical activity, while the secondary outcome measures included the Oswestry disability index questionnaire, Beck depression inventory, frequency of medicine use, strength of lumbar extensors and endurance of postural positions. These measures were taken just before the first session, 2 weeks after last session, and 6 weeks after last session.

The results:

All groups experienced significantly less pain during physical activity, improved scores in the Oswestry disability index and Beck depression inventory, after the 6-week program.

The FE and SE groups experienced significant less pain during rest after the 6-week program.

The WE and SWE groups had significant increase in postural endurance for prone, supine and sidelying positions.

What it means:

Limitations behind the study include the absence of a control group, lack of long-term follow-up, and a small sample size (n=48).

All groups, despite their differences in exercise programs, experienced positive outcomes with respect to low back pain and tolerance to everyday physical activities. While this reiterates the benefits of general exercise for the low back, the author believes the study’s positive findings may also be attributed to the education that all participants received on optimal posture with ideal pelvic alignment for lumbar lordosis and activation of erector spinae, as well as the abdominal bracing method to maintain activation of the transverse abdominis and internal oblique musculature.

See below for examples of low back pain exercises.

REFERENCES:

Suh JH, Kim H, Jung GP, Ko JY, Ryu JS. The effect of lumbar stabilization and walking exercises on chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Jun;98(26):e16173. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016173. PMID: 31261549; PMCID: PMC6616307.

Lost Posture: Why Some Indigenous Cultures May Not Have Back Pain

Back pain is a tricky beast. Most Americans will at some point have a problem with their backs. And for an unlucky third, treatments won't work, and the problem will become chronic.

Believe it or not, there are a few cultures in the world where back pain hardly exists. One indigenous tribe in central India reported essentially none. And the discs in their backs showed little signs of degeneration as people aged.

An acupuncturist in Palo Alto, Calif., thinks she has figured out why. She has traveled around the world studying cultures with low rates of back pain — how they stand, sit and walk. Now she's sharing their secrets with back pain sufferers across the U.S.

About two decades ago, Esther Gokhale started to struggle with her own back after she had her first child. "I had excruciating pain. I couldn't sleep at night," she says. "I was walking around the block every two hours. I was just crippled."

Gokhale had a herniated disc. Eventually she had surgery to fix it. But a year later, it happened again. "They wanted to do another back surgery. You don't want to make a habit out of back surgery," she says.

This time around, Gokhale wanted to find a permanent fix for her back. And she wasn't convinced Western medicine could do that. So Gokhale started to think outside the box. She had an idea: "Go to populations where they don't have these huge problems and see what they're doing."

So Gokhale studied findings from anthropologists, such as Noelle Perez-Christiaens, who analyzed postures of indigenous populations. And she studied physiotherapy methods, such as the Alexander Technique and the Feldenkrais Method.

Then over the next decade, Gokhale went to cultures around the world that live far away from modern life. She went to the mountains in Ecuador, tiny fishing towns in Portugal and remote villages of West Africa.

"I went to villages where every kid under age 4 was crying because they were frightened to see somebody with white skin — they'd never seen a white person before," she says.

Gokhale took photos and videos of people who walked with water buckets on their heads, collected firewood or sat on the ground weaving, for hours.

"I have a picture in my book of these two women who spend seven to nine hours everyday, bent over, gathering water chestnuts," Gokhale says. "They're quite old. But the truth is they don't have back pain."

She tried to figure out what all these different people had in common. The first thing that popped out was the shape of their spines. "They have this regal posture, and it's very compelling."

And it's quite different than American spines.

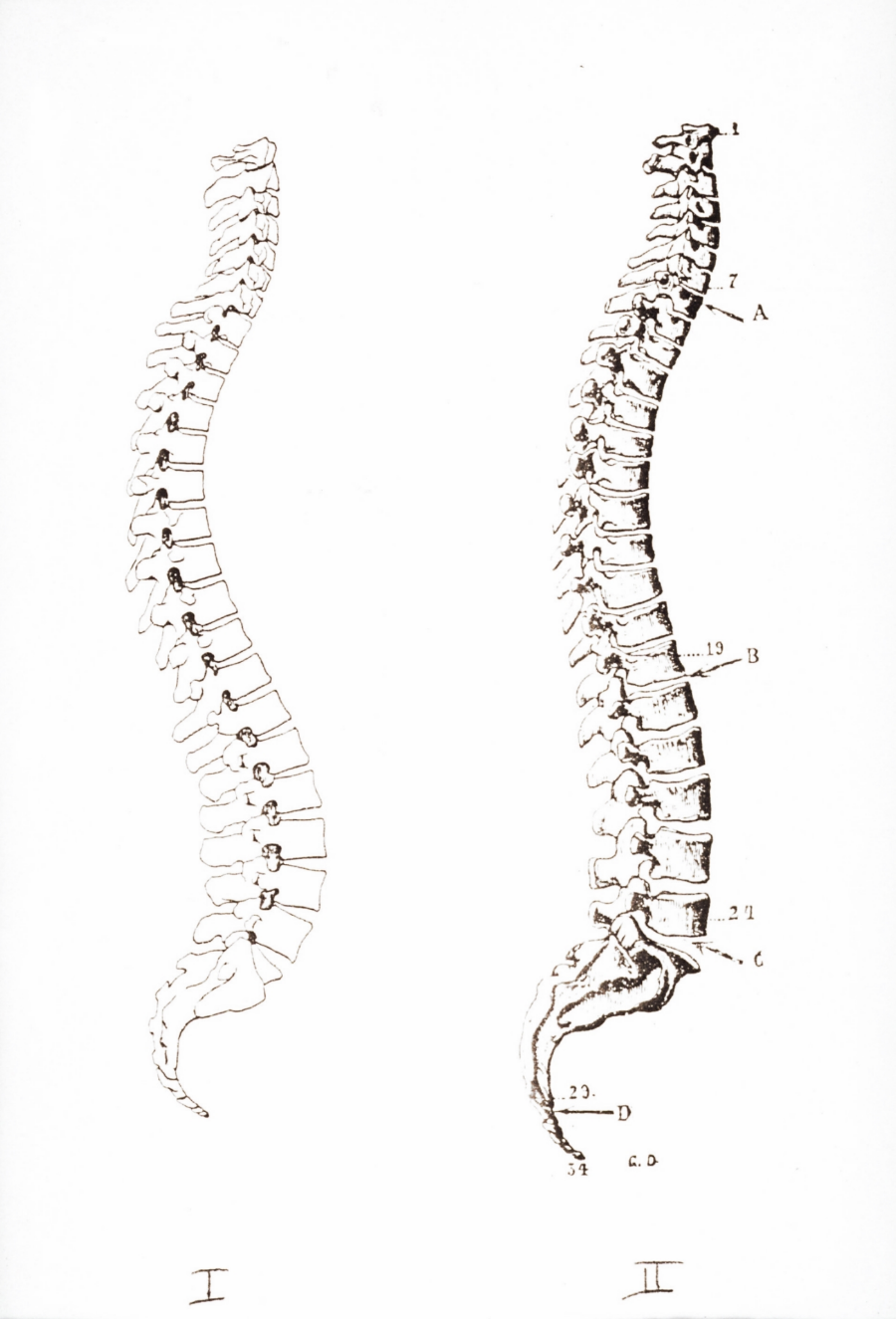

If you look at an American's spine from the side, or profile, it's shaped like the letter S. It curves at the top and then back again at the bottom.

But Gokhale didn't see those two big curves in people who don't have back pain. "That S shape is actually not natural," she says. "It's a J-shaped spine that you want."

In fact, if you look at drawings from Leonardo da Vinci — or a Gray's Anatomy book from 1901 — the spine isn't shaped like a sharp, curvy S. It's much flatter, all the way down the back. Then at the bottom, it curves to stick the buttocks out. So the spine looks more like the letter J.

"The J-shaped spine is what you see in Greek statues. It's what you see in young children. It's good design," Gokhale says.

So Gokhale worked to get her spine into the J shape. And gradually her back pain went away.

Then Gokhale realized she could help others. She developed a set of exercises, wrote a book and set up a studio in downtown Palo Alto.

Now her list of clients is impressive. She's helped YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki and Matt Drudge of the Drudge Report. She has given classes at Google, Facebook and companies across the country. In Silicon Valley, she's known as the "posture guru."

Each year, doctors in the Bay Area refer hundreds of patients to Gokhale. One of them is Dr. Neeta Jain, an internist at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation. She puts Gokhale's method in the same category as Pilates and yoga for back pain. And it doesn't bother her that the method hasn't been tested in a clinical trial.

"If people are finding things that are helpful, and it's not causing any harm, then why do we have to wait for a trial?" Jain asked.

But there's still a big question looming here: Is Gokhale right? Have people in Western cultures somehow forgotten the right way to stand?

Scientists don't know yet, says Dr. Praveen Mummaneni, a neurosurgeon at the University of California, San Francisco's Spine Center. Nobody has done a study on traditional cultures to see why some have lower rates of back pain, he says. Nobody has even documented the shape of their spines.

"I'd like to go and take X-rays of indigenous populations and compare it to people in the Western world," Mummaneni says. "I think that would be helpful."

But there's a whole bunch of reasons why Americans' postures — and the shape of their spines — may be different than those of indigenous populations, he says. For starters, Americans tend to be much heavier.

"If you have a lot of fat built up in the belly, that could pull your weight forward," Mummaneni says. "That could curve the spine. And people who are thinner probably have less curvature" — and thus a spine shaped more like J than than an S.

Americans are also much less active than people in traditional cultures, Mummaneni says. "I think the sedentary lifestyle promotes a lack of muscle tone and a lack of postural stability because the muscles get weak."

Everyone knows that weak abdominal muscles can cause back pain. In fact, Mummaneni says, stronger muscles might be the secret to Gokhale's success.

In other words, it's not that the J-shaped spine is the ideal one — or the healthiest. It's what goes into making the J-shaped spine that matters: "You have to use muscle strength to get your spine to look like a J shape," he says.

So Gokhale has somehow figured out a way to teach people to build up their core muscles without them even knowing it. "Yes, I think that's correct," Mummaneni says. "You're not going to be able to go from the S- to the J-shaped spine without having good core muscle strength. And I think that's key here."

So indigenous people around the world don't have a magic bullet for stopping back pain. They've just got beefy abdominal muscles, and their lifestyle helps to keep them that way, even as they age.

Esther Gokhale's Five Tips For Better Posture And Less Back Pain

Try these exercises while you're working at your desk, sitting at the dinner table or walking around, Esther Gokhale recommends.

1. Do a shoulder roll: Americans tend to scrunch their shoulders forward, so our arms are in front of our bodies. That's not how people in indigenous cultures carry their arms, Gokhale says. To fix that, gently pull your shoulders up, push them back and then let them drop — like a shoulder roll. Now your arms should dangle by your side, with your thumbs pointing out. "This is the way all your ancestors parked their shoulders," she says. "This is the natural architecture for our species."

2. Lengthen your spine: Adding extra length to your spine is easy, Gokhale says. Being careful not to arch your back, take a deep breath in and grow tall. Then maintain that height as you exhale. Repeat: Breathe in, grow even taller and maintain that new height as you exhale. "It takes some effort, but it really strengthens your abdominal muscles," Gokhale says.

3. Squeeze, squeeze your glute muscles when you walk: In many indigenous cultures, people squeeze their gluteus medius muscles every time they take a step. That's one reason they have such shapely buttocks muscles that support their lower backs. Gokhale says you can start developing the same type of derrière by tightening the buttocks muscles when you take each step. "The gluteus medius is the one you're after here. It's the one high up on your bum," Gokhale says. "It's the muscle that keeps you perky, at any age."

4. Don't put your chin up: Instead, add length to your neck by taking a lightweight object, like a bean bag or folded washcloth, and balance it on the top of your crown. Try to push your head against the object. "This will lengthen the back of your neck and allow your chin to angle down — not in an exaggerated way, but in a relaxed manner," Gokhale says.

5. Don't sit up straight! "That's just arching your back and getting you into all sorts of trouble," Gokhale says. Instead do a shoulder roll to open up the chest and take a deep breath to stretch and lengthen the spine.

Article written by Michaeleen Doucleff